Joseph Haydn, arias and cantatas

Joseph Haydn, arias and cantatas

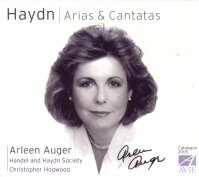

Arleen Auger Soprano

Christopher Hogwood Conductor

Handel and Haydn Society

Avie AV2066

This recording comprises:

“Scena di Berenice” Hob XXIVa:10 from La Circe, ossia L’isola incantata

Son pietosa, son bonina, Hob XXXIIb:1

Arianna a Naxos

Solo e penso Hob XXIVb:20

Miseri noi, miseria patria! Hob XXIVa:7

The following review appears in the Proms 2005 Special Issue of the BBC Music Magazine, and is reproduced by kind permission of BBC Music Magazine and Origin Publishing.

Haydn

Arias & Cantatas: Arianna a Naxos, Hob. XXVIb:2 (orchestral version);

Scena di Berenice, Hob. XXIVa: 10;

Miseri noi, misera patria!, Hob. XXIVa: 7;

Solo e pensoso, Hob. XXIVb:20

Arleen Auger (soprano); Handel and Haydn Society / Christopher Hogwood

Avie AV 2066 (Reissue 1990)

53:02 mins

Arleen Auger’s all-Haydn recital, mixing the familiar (Arianna a Naxos — performed here in an 18th-century arrangement for string orchestra — and the great Scena di Berenice) and a clutch of rarities, rightly won plaudits on its original release in 1990. With her limpid, gently rounded tone, immaculate coloratura and unfailing elegance of phrase, Auger had few rivals in this repertoire. Other singers, including Bernarda Fink (on a new Harmonia Mundi disc, reviewed last issue), have brought more anguished abandon to the soliloquy of the bereft Berenice. Auger’s classical princesses, here and in Arianna, retain a certain stoical dignity. But this is not to imply her singing is remotely chilly. While never compromising beauty and purity of line, she conjures plenty of passion for the heroines’ final outbursts, where her depth and incisiveness of tone may surprise the unwary.

If the cantata Miseri noi sounds too serene and (in the final section) chirpy for its grim text, the fault is Haydn’s. Auger’s singing is, as ever, a model of musicality and grace. She is just as delightful in the touching Petrarch setting Solo e pensoso and perky buffa aria bemoaning men’s faithlessness. Hogwood and his Boston period band provide neat and spirited accompaniments. A moving reminder of a supreme Classical stylist who, like her exact contemporary Lucia Popp, died far too young.

Richard Wigmore

performance *****

sound *****

CD sleeve notes

During his long career as operatic Kapellmeister for Prince Nicolaus Esterházy in Hungary, Haydn performed many popular operas of the day in the princely theatre at Esterháza (which seated 500 and was free to any decently dressed man or woman). Sometimes Haydn took considerable liberties with the scores, fleshing out the often rather simple orchestration of the Italian arias by adding wind instruments or shortening pieces he thought too lengthy or verbose. Occasionally he replaced an entire aria with one of his own composition, and this was particularly true if Haydn’s pretty, olive-skinned Italian mistress, Luigia Polzelli, participated. She was a soubrette of limited talents, but Haydn loved her tenderly and wrote music obviously calculated to bring out all her best qualities. The music he composed for her makes her sound like a great flirt.

Usually we have libretti printed for the occasion with cast lists, but in the case of the pasticcio entitled La Circe, ossia L’isola incantata based on two operas, one, La maga Circe, by Pasquale Anfossi and the other, Ipocondriaco, by Gottlieb Naumann, which Haydn conducted at Esterháza in 1789, we are unable to say whether Luigia sang the part of Lindora, who receives a whole new aria by Haydn entitled “Son pietosa, son bonina”. This pretty two-part work is one of at least three large-scale insertions which Haydn composed for this pasticcio.

We have no information when or for what occasion Haydn wrote his cantata Miseri noi, misera patria except that it was before 1786 (when Haydn’s Viennese publisher sold a copy in manuscript to Germany). It is probably the work Haydn sent to the impresario J. P. Salomon in London in 1790 to be sung by Nancy Storace (Mozart’s first Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro). Only discovered and published after World War II, this beautiful cantata describes the destruction of a city by pillaging troops.

On the other hand, the famous Scena di Berenice was especially composed in London for the celebrated dramatic soprano Brigida Banti. Haydn gave it at his benefit concert in May 1795 in the King’s Theatre. Afterwards he noted in his diary that “she sang very scanty”. Banti must have had an off night, because otherwise she was the toast of the town and had London at her feet. This scene — a dramatic evocation of a loving woman abandoned by her partner — is Haydn’s greatest and most profound contribution to the form, ending in a fiercely expressed aria in F minor.

The composer’s last concert aria, “Solo e pensoso”, was composed in 1798, the year of The Creation’s first performance. This pensive setting of a Petrarch sonnet was given its first hearing at a pre-Christmas pair of concerts of the Society of Musicians in Vienna, when it was sung by the mezzo-soprano Antonie Flamm, with whom Haydn had earlier collaborated in the vocal version of the oratorio The Seven Last Words of the Saviour on the Cross.

The way in which these pieces have survived is often rather curious. When Haydn left Hungary to visit London in 1790, he took with him a collection of these arias, removing the scores physically from the operas to which they had been attached. Hence in the score of La Circe from the Esterházy Archives in Budapest, the aria “Son pietosa” is missing, but from the set of manuscript parts one double bass shows where it ought to go. Haydn gave one copy of the aria to a friend in England; and another ended up in Göttweig Abbey in Austria; a third was given to a visiting Swedish diplomat in Vienna and is now in a Swedish castle. The first edition was not issued until the 1950s.

In the case of the cantata Miseri noi, misera patria, the only two manuscripts in the world — one authentic with corrections and additions by Haydn but not complete, the other complete — are in the Library of Congress in Washington. The first performance of the work took place during a Haydn series which the BBC produced in 1958; subsequently the cantata was published for the first time in 1960.

The great Scena di Berenice has survived in Haydn’s autograph manuscript (in the Vienna Stadtbibliothek) but was not printed until the 1930s. Since then, a new manuscript which Haydn gave to a visiting English singer in Vienna in 1797, has come to light; it is important because it restores the cut of three bars at the beginning which Haydn made post 1797 in the autograph manuscript. (The cut means simply that the Scena begins forte rather than piano, but the opening material which Haydn removed is thematically related to what follows, and is included in this recording.)

The setting of the Petrarch sonnet “Solo e pensoso” has survived only in Haydn’s autograph manuscript (in the Paris Bibliothèque Nationale); it too was not printed until 1961. It features two clarinet parts (also present in the Scena di Berenice where, however, they are more reticent) which again reminds us of the proximity to The Creation with its involved use of clarinets, instruments which Haydn had only occasionally used in his orchestra at Esterháza. He inherited in the Vienna orchestra the clarinet players for whom Mozart had written his famous wind band music, which had changed the whole concept of orchestration and especially wind writing.

Arianna a Naxos, the most puzzling of Haydn’s cantatas, was first sung by the Italian castrato Pacchierotti during his last visit to England in 1791 with Haydn accompanying him on the fortepiano. The press declared the piece “so exquisitely captivating in its larmoyant passages, that it touched and dissolved the audience... Pacchierotti never, in his most brilliant age, was more successful”. The work was repeated a few days later at the Pantheon, in a programme that also included a Haydn symphony played by an orchestra of 300. Although Haydn’s published version is for keyboard and voice, the work is instrumental in concept, and a recently discovered letter from the composer to the music publisher John Bland says: “ The cantata Ariana auf Naxos I intend later on to orchestrate for a full band”. It seems that Haydn never managed to make this orchestration, and it was not until the next century that an anonymous version for full orchestra (transposed to F) was published in Vienna.

More interesting, however, is a scoring for strings from the Martorell Collection in the Library of Congress — the same volume that provides the material for Miseri noi, misera patria. Much of this collection appears to be connected with direct Haydn sources (via the King of Naples) and, although the arrangement is anonymous, there are many elaborations and recompositions which make it more than a simple transcription; the implicit canonic imitations in the introduction, for instance, are given in full, and in later recitative sections we find additional tempo indications, and a filling out of the textures implied in the keyboard version. It is also specifically for string orchestra and not simply string quartet (as is the version in Zittau made by F. W. Hildebrand) since the score distinguishes between full bassi and a line for violoncello. Clearly the arranger was more than a mere hack, and even without Haydn’s imprimatur, an authentic 18th-century orchestral version of this unique cantata is an important addition to the repertoire. For this recording the cantata has been newly edited; vocal embellishments and cadenzas have been based on suggestions in the Viennese orchestral version, as well as variants contained in the Library of Congress score.

© H. C. Robbins Landon & Christopher Hogwood, 1990

Performers’ biographies

The ravishing angelic voice of Arleen Auger was stilled on 10 June 1993, when she succumbed to brain cancer, aged 53. As winner of the 1967 Viktor Fuchs Vocal Competition she went to Vienna, was soon “discovered” and immediately signed by the Vienna Staatsoper and made her debut there as the Queen of the Night with Josef Krips conducting. In 1969, she made acclaimed debuts with the New York City Opera (Queen of the Night) and the Metropolitan Opera (Marzelline) with Karl Böhm.

During her illustrious career she was a welcome and familiar figure in the world’s most prestigious concert halls and opera houses including La Scala, the Metropolitan, Vienna’s Staatsoper, Carnegie Hall, Avery Fisher Hall, Le Châtelet, the Concertgebouw, Wigmore Hall and Royal Festival Hall. She also appeared at over sixty major music festivals and made thirteen recital tours worldwide. In 1986 she was the first American to sing at a British Royal Wedding, when she sang Mozart’s Exsultate, jubilate to a television audience of over 700 million.

Her discography of over 300 recordings ranges from Bach to Schoenberg and she has been honoured with countless awards including the Orphée d’Or, Deutscher Schallplattenpreis, Grand Prix du Disque, multiple Edison Prizes and a posthumous Grammy.

Since founding The Academy of Ancient Music in 1973, Christopher Hogwood has gained international recognition for his performances of baroque and early classical repertoire with period instruments. But for more than forty years he has also been performing music of the twentieth century, with a particular affinity for the neo-baroque and neo-classical schools including many works by Stravinsky, Martinu and ‘Entartete’ composers. As a musicologist he is currently involved in editing works ranging from Purcell and Handel via Mendelssohn to Elgar and Martinu.

He has a celebrated catalogue of more than 200 recordings with The Academy of Ancient Music, and his recent recording projects range from the symphonies and overtures of Niels Gade to ‘The Secret Bach’, the first in a series of baroque and classical music for clavichord. The neo-classical is also represented in an ongoing series of recordings with the Kammerorchester Basel, which includes works by Martinu, Stravinsky, Honegger and Britten.

In addition to his position as Director of The AAM, he continues as Principal Guest Conductor of the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi and the Kammerorchester Basel; he is also Conductor Laureate of the Handel and Haydn Society with whom he has been working for more than twenty years.

Under the leadership of music director Grant Llewellyn and conductor laureate Christopher Hogwood, the Handel and Haydn Society is a leader in historically informed performance, specializing in music for chorus and period orchestra from the Baroque and Classical eras. Each Handel and Haydn concert is distinguished by the use of instruments, techniques, and performance styles typical of the period in which the music was composed. Now in its 190th season, the Society has a long tradition of musical excellence. In the nineteenth century, Handel and Haydn gave the American premieres of Handel’s Messiah (1818), which the Society has performed every year since 1854, Haydn’s The Creation (1819), Verdi’s Requiem (1878) and Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1889). Recent seasons have included collaborations with prominent jazz artists, a series of semi-staged operas, weekend-long festivals, and world and American premieres. The Society’s ambitious Educational Outreach Program brings the joy of classical music to more than 10,000 students each. Handel and Haydn received a 2002 Grammy Award for its recording of Sir John Tavener’s Lamentations and Praises.